Wild Trillium Common in Great Black Swamp Habitat

By Rick Barricklow

Certainly, one of my favorite Oak Openings Region spring ephemerals, is the Large-flowered Trillium. It will flower, produce seeds and store nutrients for the following spring within a short time. Then it returns underground for the remainder of the year leaving only a bare stalk with seeds into the summer.

A member of the Lily Family (Liliaceae), the name trillium comes from the Latin word for three (tres). All parts of the plant appear in threes: the sepals, petals and even the whorl of leaves.

Although our Oak Openings Region has two other species of trilliums, Drooping (Trillium flexipes) and Sessile (Trillium sessile), the Large-flowered is most abundant and readily identified in our area. Designated the State of Ohio Wildflower in 1987, the Large-flowered Trillium grows in all 88 counties. Goll Woods State Nature preserve located near Archbold, Ohio, is one location where the three species can be seen together.

The Large-flowered Trillium can be found growing in moist, shady, high quality, rich-soiled woodlands. Finding them in the wild indicates a healthy local ecosystem, one without extensive human encroachment, not overgrazed by deer and one where they haven’t been crowded out by invasive species.

Spreading by underground rhizomes to form spectacular colonies, their upright flowers seem to mostly face in one direction and can make you smile. Green leaves cradle the green sepals below the white petals. The center of the flower, being yellow, helps in identification. Petals fade to a delicate pinkish-purple with age after pollination.

When it comes to pollination, they are considered generalists, meaning more than one type of insect is suitable to perform pollination duties. This increases the plant’s chances of cross pollination since it blooms early when it can still be colder outside and insect activity is low. The flowers contain no nectar, and unlike other early blooming spring ephemerals that lose their flowers quickly, the Large-flowered Trilliums strategy is a rather long floral life of 17-21 days. This long flowering period increases the chance of attracting a bumble or other native pollen foraging bee to do the necessary work.

Seeds that are lucky enough to be produced are contained within a fleshy capsule on top of the flower stalk. This capsule falls apart dropping the 12 or more seeds when ripe. Because the seeds have a fat-rich structure attached to them called an eliasome they are picked up by native ants and taken to their nests. The eliasome is then eaten, leaving only the seed to be carried out of the nest and deposited in the ants’ garbage dump known as the midden, a great place to germinate. The trillium and native ants have developed a mutualistic relationship in that both species benefit from one another. Ecologists call this specific ant system of seed dispersal myrmecochory.

A very slow growing plant, the seeds require double-dormancy, meaning they take at least 2 years to fully germinate. A slender cotyledon appears above ground the second spring and provides nutrients to the germinating plant. A single oval true leaf appears the third spring and from the fourth spring onward there will be three leaves. The underground rhizome continues to develop and store nutrients until it has enough storage capacity to initiate flowering, usually 7-10 years. A large colony blanketing a forest floor is like the wildflower equivalent of an old-growth forest. White-tailed deer choose to eat the larger plants, leaving the shorter ones behind. This provides evidence that can be used to assess deer density and its effect on understory growth in general.

Having been a fan of trilliums for many years starting on my springtime visits to The Great Smoky Mountains National Park, I really enjoyed discovering them growing in our Oak Openings Region and still do. After attending the Goll Woods garlic mustard pull stewardship event last spring, I was excited to show Denise Gehring one of the “special” places I knew of in Sylvania to see a colony of trillium. This ultimately led me to become a member of the Wild Ones.

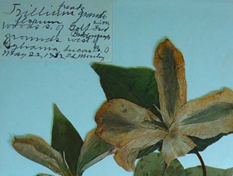

Occasionally there are trilliums to be found affected by a pathogen causing altered structures. Double sepals and petals, green petals or variegated green and white petals are some of the results. Denise was able to locate a plate by Edwin L. Moseley 1869-1948 (the famed local botanist who studied and reported on the flora of our Oak Openings Region) remarking on the “freak” trilliums he had discovered in Sylvania. The location where I took Denise happens to be one where these individuals are growing.

Occasionally there are trilliums to be found affected by a pathogen causing altered structures. Double sepals and petals, green petals or variegated green and white petals are some of the results. Denise was able to locate a plate by Edwin L. Moseley 1869-1948 (the famed local botanist who studied and reported on the flora of our Oak Openings Region) remarking on the “freak” trilliums he had discovered in Sylvania. The location where I took Denise happens to be one where these individuals are growing.

A fascinating life cycle with ant partners, their subtle beauty and the special places they inhabit make trilliums very attractive to me and I look forward to spring every year in anticipation of their arrival.

Thank you to the Wild Ones for allowing us to reprint this story. Photos by Suzanne Nelson and Hal Mann. View the entire May 2019 newsletter here.